Lifestyle influences microbiome more than geography: Study

A new study from Washington University in St. Louis found that the gut makeup of apes living in US zoos more closely resembles that of people who eat a non-Western diet when compared to the intestinal bacteria of their wild ape cousins.

Study details

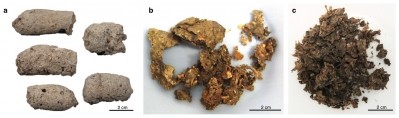

Without disturbing the subjects, researchers followed apes in known groups and discreetly plucked fecal samples from 18 wild chimpanzees and 28 wild gorillas in Nouabale-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo. The research team also obtained fecal samples from 81 people who lived on the outskirts of the park.

At the same time, the researchers in the US collected fecal samples from 18 chimpanzees and 15 gorillas living at either the St. Louis Zoo or the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago.

Going the distance

The fecal samples from the Republic of Congo had quite a journey ahead. They were stored in liquid nitrogen, carried to the park headquarters, and transported by dugout canoe down the Sangha River and then by truck to Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of Congo, where they were held in a freezer until they could be shipped to a lab in the US.

The research team studied the samples and identified various bacteria and the antibiotic genes present in the gorilla, chimpanzee and human samples. From there, they compared their findings to publicly available data on people who live in the US, Peru, El Salvador, Malawi, Tanzania, or Venezuela and maintain hunter-gatherer, rural agriculturalist, or urban lifestyles.

Findings

The study found that contact with people influences the gut microbial communities of gorillas and chimpanzees.

The gut microbiomes of people fell into two groups. One group consisted of hunter-gatherers and rural agriculturalists who mostly eat a diet rich in vegetables and light in meat and fat. This group included the people from the outskirts of the national park in the Republic of Congo.

The second group were urban people who eat a Western diet heavy in meat.

The third group was formed by gorillas and chimpanzees in the wild, distinct from both human groups.

When comparing captive apes to the above groups, the researchers discovered that the gut makeup of captive apes more closely resembled the microbiomes of people who ate non-Western diets in the first group than their wild cousins.

The authors point out that the findings suggest that human contact influences the gut microbiomes of gorillas and chimpanzees, and that the microbiomes of wild apes provide clues to human-ape interactions that could inform efforts to protect the endangered species.

“Chimpanzees are endangered, and Western lowland gorillas are critically endangered; their main threats are habitat destruction, poaching and disease,” said co-author Crickette Sanz, PhD, an associate professor of biological anthropology in Arts & Sciences at Washington University.“Measuring the gut microbiome could be a way to monitor apes’ exposure to anthropogenic threats so we can identify areas of concern and develop effective, evidence-based mitigation strategies.”

Further findings

Even wild apes that have never encountered antibiotics harbor microbes with antibiotic-resistant genes. The researchers said this study led to the discovery of several previously unknown antibiotic resistance genes in the wild apes and people from Congo, including one that provides resistance to colistin, an antibiotic in last resort cases.

The findings could lead to new ways of identifying novel antibiotic resistance genes before they become widely established in bacteria in people, giving researchers time to develop tools to counter such genes before they threaten human health.

First author Tayte Campbell, PhD, then a graduate student at Washington University School of Medicine, noted that this rare opportunity to study wild apes offers a glimpse into the future. “When we find these novel antibiotic resistance genes in the environment, we can study them and possibly find ways to inhibit them before they show up in human pathogens and make infections very difficult to treat.”

“Wild apes are the closest thing we have to pre-antibiotics humans,” said senior author Gautam Dantas, PhD, a professor of pathology and immunology, of molecular microbiology, and of biomedical engineering at Washington University School of Medicine. “It’s difficult to figure out exactly how antibiotics affect the human gut microbiome when almost everyone is born with bugs that already have antibiotic resistance genes.”

Source: The ISME Journal

(2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0634-2

“The microbiome and resistome of chimpanzees, gorillas, and humans across host lifestyle and geography”

Authors: T. Campbell et al.